8th January 2019, words by Clare Hyde, Max French, Simon Johnson

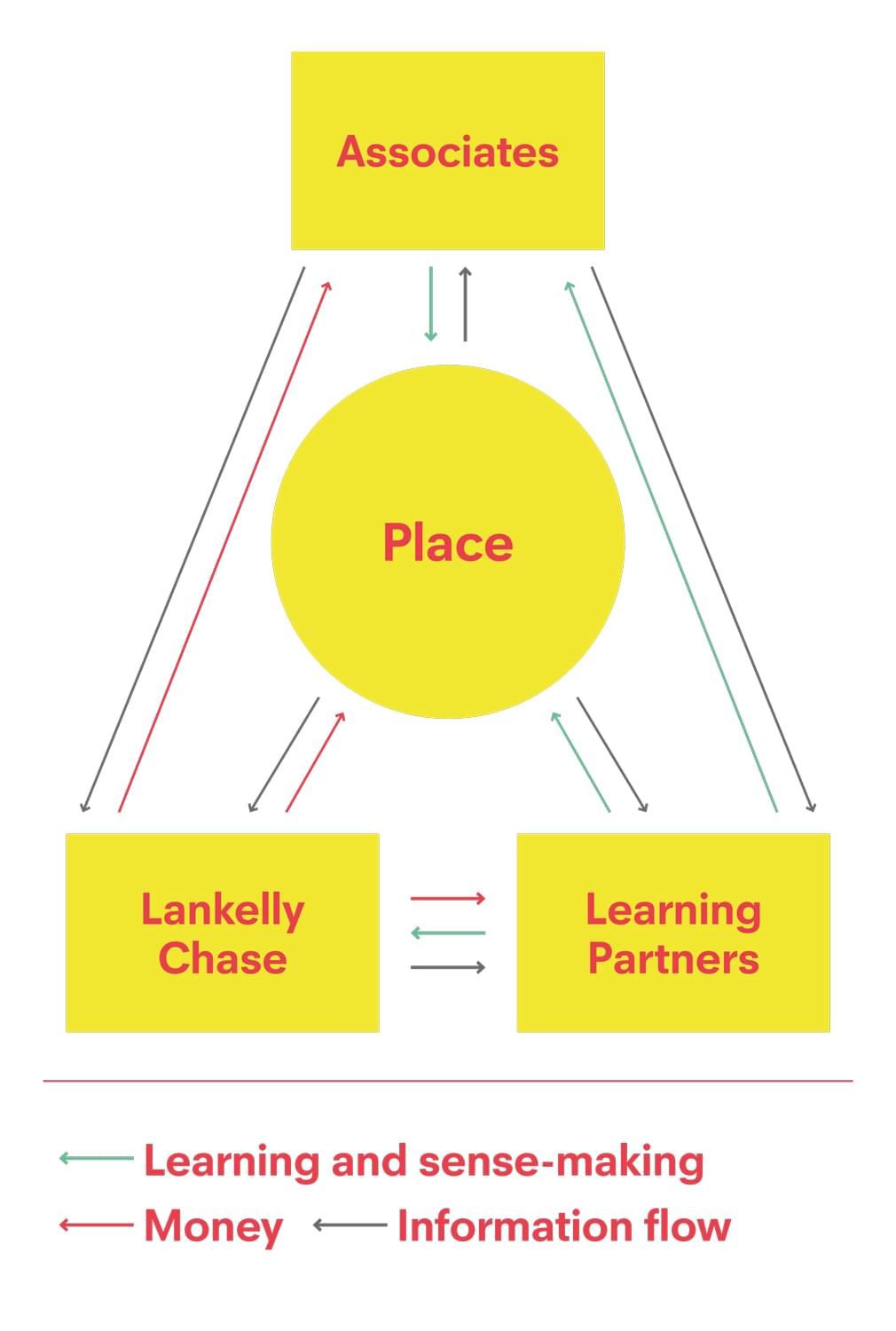

Part of Lankelly Chase’s Action Inquiry on ‘place’ has involved funding associates to work with local actors to embed the 9 System Behaviours. This piece is a synthesis of our experiences in the action inquiry as they relate to those conditions. We chose to reflect on the topic of trust which is central to System Behaviour 5: open, trusting relationships enable effective dialogue. Our conversations about trust have centred around two complexes of relationships: relationships among professionals, and relationships between professionals and service users.

Part of Lankelly Chase’s Action Inquiry on ‘place’ has involved funding associates to work with local actors to embed the 9 System Behaviours. This piece is a synthesis of our experiences in the action inquiry as they relate to those conditions. We chose to reflect on the topic of trust which is central to System Behaviour 5: open, trusting relationships enable effective dialogue. Our conversations about trust have centred around two complexes of relationships: relationships among professionals, and relationships between professionals and service users.

In every locality where associates are working, a lack of trust amongst local actors has been a key barrier to progress. Distrust has prevented relationships developing across traditional boundaries – such as between organisations, professions or sectors. In some localities, distrust has also soured established relationships and inhibited collaboration. Some interventions that associates became involved with had emerged from (and sometimes responded to) a climate of distrust between citizens and service professionals. Associates described service users disengaging from services, only to manifest somewhere else when their situation had spiralled into crisis.

Distrust can become a prism through which various local actors – professionals and those with lived experience of disadvantage and exclusion – view their system. Legal, procedural or financial barriers to professionals working together to improve service conditions became justification for not engaging with new ways of working and thinking rather than as challenges to be overcome together. For service providers, distrust could promote a retreat into siloed thinking and ‘us and them’ relationship dynamics, locking down systems and perpetuating the status quo. For people living with severe and multiple disadvantage, distrust reinforced a sense of alienation, exclusion and helplessness.

Associates described various ways they worked to build trust in their place-based work. Most significantly, associates cited their independence and neutrality as a key asset. Associates were seen by local actors as offering a safe space for confidential and personal conversations, as allies to vent frustrations to, and as critical friends to work through problems and float ideas with. This was an uncommon opportunity in cash strapped local governance systems: associates told us that local actors sometimes initiated conversations which they couldn’t express to anyone else in the locality. Where relationships between key actors could not be repaired, associates capitalised on their position as trusted actors to mediate communication across boundaries and refract divergent perspectives which local actors might otherwise be unreceptive or hostile toward.

However, trust not only needed to be built but re-built in the wake of constant system flux. Local public service systems were described by associates as unstable landscapes undergoing constant churn: key local actors would move posts, local partnership structures would emerge or fall off, relationships would break down, new initiatives would spring up and take priority. Some associates responded by looking for what they called the ‘fixed points’ in the system – individuals, organisations or local fora which had leverage and staying power. In some cases, this moved the focus of their relationship -building efforts from senior officials and key strategic partnership structures towards people rooted by their role or commitment. In other cases, this involved looking to community and voluntary organisations, or people with lived experience who could keep issues live and visible in the area.

A lesson hard learned in some localities was also that trust can take a long time to build, but can be destroyed very quickly. Associates could pinpoint some key decisions and actions taken by local actors which were highly destructive of trust and which quickly undermined relationships. Associates also maintained trust by helping actors to reflect on the implications of their activities on local trust. Associates helped local actors cope with system flux by convening ongoing dialogue and review to ensure mutual understanding about roles, expectations and relationships.

From our reflections, the strength of trust appears closely related to how well-equipped service systems are to respond to individuals facing severe and multiple disadvantage, and to any other complex issue which requires the combination of knowledge and resources from different domains of experience.

Trust was chosen as the first system behaviour to reflect upon because it was seen by one associate as the most important of the 9 System Behaviours. We can only devolve decision making (Behaviour 4) and power (Behaviour 5) if we trust those we ask to take on responsibility. Trust can facilitate the development of shared vision (Behaviour 3) and learning through feedback (Behaviour 9) because actors can communicate more openly and honestly. It also follows that trust can facilitate collaborative and systemic leadership (Behaviour 8) through trust-based accountability and promoting a sense of responsibility, rather than by enforcing hierarchical accountability (Behaviour 6). If only we could establish trust, many of the other 9 Behaviours would follow.

Other associates didn’t quite agree: while trust was important, it should be understood as both an input and an output of each of these behaviours, and our interventions should not be expressly concerned with trust above the others.

Management practice in public services and social interventions has often operated under the implicit assumption that trust was absent. Monitoring and audit regimes, pre-determined funding ‘criteria’, standard operating procedures, results-based performance management: all promise good stewardship of financial resources, high-quality services, and the prevention of harm and abuse. But they also erode trust, deprofessionalise staff and limit our capacity to act in those domains where relationships – rather than procedures – are essential to improving outcomes.

Is trust the basis from which to begin thinking differently about how to manage and govern the relationships which promote the effective use of resources, or is it just one small part of such a basis? Our future reflections on the System Behaviours will help us to explore this more fully.

We have just reviewed the last year of the Place Action Inquiry. To learn more, the summary report can be found here.

Comments (0)